Hello! How are you doing today? I hope this finds you well. I am revelling in the coolness of this Monday morn. Bring on the rain!

We spent Saturday in London going to see the Anselm Kiefer/Van Gogh exhibition at the Royal Academy, a gift from my children to my husband for his 60th and it was so incredibly hot. They all laughed at my little mini fan, but I think they were secretly envious of it. By the time we got home at 9pm, I felt like I’d melted into the pavement somewhere on Piccadilly and been scooped back up and carried home somehow. I was exhausted and so out of practice of big city being.

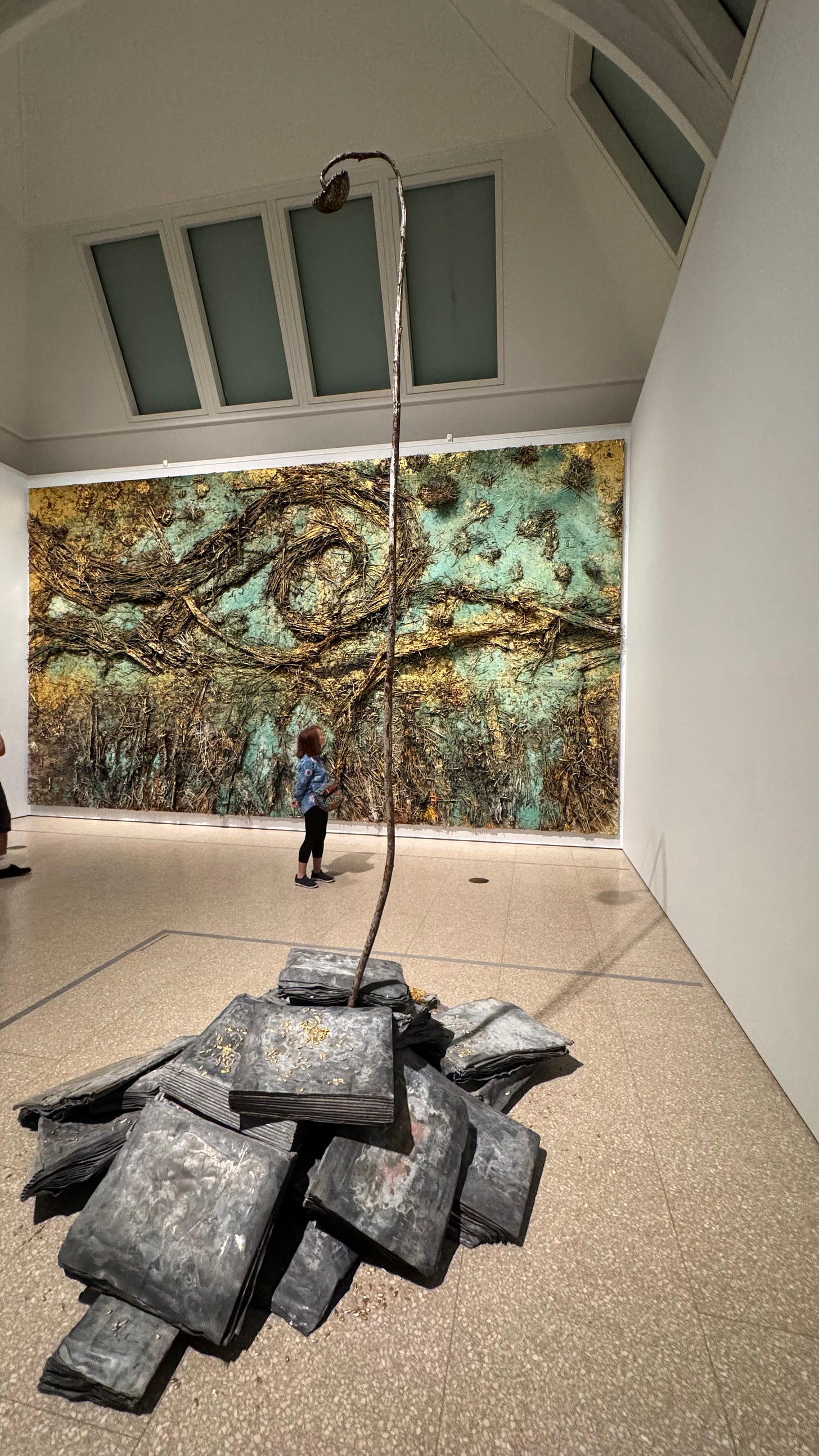

My husband is a big Kiefer fan, and over the years of traipsing around exhibitions, including now 2 this year, so have I become. Anselm Kiefer is a German painter and sculptor who creates intricate and huge works that explore German history, particularly the Nazi era and its aftermath, as well as mythology, alchemy, and the human condition. He incorporates natural elements with paint, words, photographs, and woodcut in an aesthetically beautiful but emotionally challenging way. Rather than forget the past, his work questions the present with it. In his own words, “If we don’t remember what we have done, we will do the same thing again.”

Layering is a big part of the production of Kiefer’s work, with straw, ash, lead, clay, and shellac marrying with paint and prose at scale. Many paintings include his writing, in German script, giving context and demanding more from us as the viewer.

Kiefer’s work demands that we look. Not glance, or nod politely, but truly see. His canvases, heavy with unexpected materials, insist we bear witness to what we’d rather forget: history’s shadow, human frailty, and the quiet complicity of silence.

It’s not comfortable. And that’s the point. (But there is a beauty to it.)

The show of Kiefer’s early work that we saw earlier this year was dark and challenging, while the show alongside Van Gogh, who work is equally layered if through mark rather than material, was a little lighter - in visual tone at least. There was gold leaf everywhere! But underneath the gold leaf, and underneath each patient, conscious mark of Vincent’s, there was a desire for us to see something beyond the obvious aesthetic.

And how can we look at a Van Gogh painting and not intertwine what we know of his mental health challenges with his work? Are they more beautiful in some way because of his struggles or because his struggles allowed him to step beyond the veil of the norm and connect with nature, beyond beauty?

There’s something about the idea of ‘beyond beauty’ that resonates with me; as though beauty isn’t the point but the by-product. What we’re really being asked to see is a truth, and truth is rarely tidy or beautiful.

In many ways, parenting through adversity is its own kind of witnessing that brings us to new truths. We find ourselves standing beside our children in moments that are unbearably raw, when their pain eclipses language, when nothing we say or do can make it better. And still, we stay. Of course we do.

Not to fix.

But to witness.

To not turn away is one of the greatest acts of love, and yet, it’s also one of the most painful. We are wired to protect, to soothe, and to shield. When our child is struggling, be it with poor mental health, identity, loss, fear, or something we can’t quite name, our first instinct is often to act - to research, to rush, to reach for answers. But sometimes, the simplest and most human thing we can offer is presence - brave, quiet, sacred presence - and that takes everything.

I don’t think we as a society talk enough about the cost of witnessing without looking away. Despite years of supporting other parents and my own lived experience, I can still be blindsided by the depths of pain parents go through. There is a tiredness that creeps into the bones, not only from lack of sleep, but from holding space for someone else while quietly trying to hold it together for yourself. There is grief, too - not just for the suffering we see in our child, but for the life we imagined they’d have, and we’d have too.

And yet we endure. Because love insists on it.

Much like Kiefer’s work, parenting through adversity is layered. You can’t see everything at once. There are days when all you notice is the lead - how heavy it feels. Other days, there’s a glimpse of gold leaf. A moment of laughter. A small connection that catches you by surprise. You start to realise that both can exist at once.

So perhaps, just like Kiefer, just like Van Gogh, we are artists too? Composing a life out of difficult materials, trying to make something meaningful out of what we never asked for. The ash of disappointment, the straw of everyday chaos, the slow-drying glue of guilt and longing. We arrange it as best we can and make our own unique marks of meaning.

Kiefer said, “Art is difficult. It’s not entertainment.” And I think about how that mirrors the kind of parenting so many of us are doing or have done - not the glossy, filtered version, but the silent, solo, trying-again kind. If you are in a season like this, please know that your presence matters - especially if your child doesn’t show it.

To witness without turning away is like art - it’s not passive, it is radical and hard. And we make it each day in our homes, in our thoughts and in our lives, not to perform but to connect, beyond beauty and into hope.

So continue to push on, like the artist you are. Parenting, like art, is difficult. Because beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and like the finest works, its worth is often only fully seen with time, perspective, and an open heart willing to look beyond the surface.

If you’d like to listen to this post, you can do so by clicking below.

The words ‘To witness without turning away’ and ‘ beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and like the finest works, its worth is often only fully seen with time, perspective, and an open heart willing to look beyond the surface’ jumped out at me. We need to be there for our children at all times in the thick of it but we can also be there to witness over time (there is no set time just patience) the changes, the moments of joy and the beauty brought to the surface after being there for them in their time of need, for showing them they are enough as they are. All these beautiful moments are worth it. X

So resonates in this world. We must never turn away. We already know what happens when we do.